ruangrupa (from left to right): Ajeng Nurul Aini, farid rakun, Iswanto Hartono, Mirwan Andan, Indra Ameng, Daniella Fitria Praptono, Ade Darmawan, Julia Sarisetiati, Reza Afisina, 2019, Photo: Jin Panji

There was a huge surge of collective pride in Indonesia as well as Southeast Asia when it was announced that ruangrupa had been selected to helm documenta 15. In your opinion, why do you think the time is right for a collective from Indonesia to set the direction for one of the art world’s most significant exhibitions?

What shifts have you observed in the global art world that may have contributed to this? Ade Darmawan: Socially-engaged practice, or community-based practice, has been developing for a while. We can see this back at the Gwangju Biennale in 2002, and in many alternative spaces globally. Collective practice is something that developed in the last two, three decades, but there have also been ups and downs. Like in Southeast Asia, there aren’t many (collectives) from our generation that are still alive and kicking. A lot of initiatives are falling apart, but it also shows how this practice is not supported by the whole ecosystem in many ways. But you cannot deny that there is a lot of influence from this initiative of collectives, it is rooted in a tradition of how collectives are part of the process of nurturing a certain practice towards criticality, towards artistic practice as well. If you can track back many people in Southeast Asia, many come from those roots, so it’s been very influential in many ways, but never really focused as a particular movement.

When we started ruangrupa twenty years ago we wrote a text, and there were two things that we pointed out: one is that art is becoming elitist, bureaucratic and institutionalized, and the second was that art is becoming very commodified. But if I see it right now in Indonesia, it’s even worse than that! When we wrote that, we didn’t have an art fair, but now we have two in Jakarta! [chuckles] And we have many Biennales and so on. These two decades we have so many things happening – and globally as well – and it’s much more institutionalized and commodified. I think these are factors that many people globally are also anxious about, how art is being practiced, and institutionalized. Even in Venice and documenta, there has been a lot of criticism about how it has been commercialized; even at the level of institutions like Biennales, there has been a lot of anxiety. So people try to find some other alternatives or other ways, and one of the ways is collective practice, which has struggled for many years, and maybe one of the factors that went into ruangrupa’s selection is also that we’re not just talking about it. There is a system or mechanism that we actually practice, so they see us as an entity or initiative that practices it also, rather than just discussing about it.

The selection process is really secretive [chuckles] but they see Southeast Asia or Indonesia in particular as having a really strong and rooted tradition – it’s not something coming from theory, it’s really like a cosmology, and that’s what they would like to have. And that’s also how we work, it’s coming from a different cosmology. I think they felt that they should see the perspective of other cosmologies.

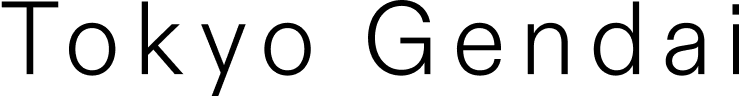

ruangrupa, lumbung: The rice barn in Indonesia as a model for resource sharing. Concept for documenta fifteen, image: Iswanto Hartono, 2020.

For documenta 15, ruangrupa introduced the concept of the ‘lumbung’ to underpin its curatorial vision and direction. Could you say a little more about what a ‘lumbung’ is and what it means for you, and for the approach of documenta 15?

Ade Darmawan: A lumbung is a rice barn in agricultural tradition. It’s still practiced now, in many villages, and this is also resonant with other terms and similar concepts in other places: how it’s a mechanism of collective sharing of resources, defining sufficiency, generosity and surpluses, in a cycle of agricultural tradition. But as a term or an idea, the word lumbung is also practiced in our head, how it’s actually collective shared resources — tangible as well as intangible resources that we have. In urban areas also it’s still happening and being practiced, so it’s not something exotic — we practice that as well in GUDSKUL with two other collectives, Serrum and Grafis Huru Hara. Since the beginning we practiced that but we never called it ‘lumbung’. In the last five years we tried to make a more systematic mechanism in how we share resources like programmes, ideas in collaboration and so on so forth, including finance. It’s also really about sustainability, ideas on how we see the sustainability of ideas, and finances.

Iswanto Hartono: Architecturally as well, the word lumbung is a practice but it’s also a very particular and specific type of architecture. And its function as well, there is one type which is used as a lumbung, as a barn; and there is one which is a social space; and the third, is a domestic and a social space. This type of lumbung is spread out over the archipelago but is widely practiced in Southeast Asia and Asia as well. This is really embedded into our daily life, and the common share, anthropologically, and the way people live in Southeast Asia and Asia, is really attached to this structure. Different places like Bali, Toraja or Sunda have different structures as to where the lumbung is located and how people work with it, but it’s very central and a very important thing for society.

Ade Darmawan: In documenta, we approach lumbung not as a theme to be illustrated or discussed, but more as a way of working or mechanism. So we created mechanisms or protocols for how to practice ‘lumbung’ in exhibitions for example, or in communication and education. It really changed how we did curatorial research as well. We don’t go around looking for one particular artwork that can illustrate the lumbung practice, it’s not about that. It’s really about selecting also how artists work: ethics, politics, and how the ecosystem works – is it collective or not. So a lot of relations have been changed as well. For example we don’t do commissions, because commissioning logic is also coming from thematic logic, and the relationship between the artist and the commissioning institution makes the artist like a service provider. We changed that, and now it’s more about intention: we all agree on a certain value, so we set up a value that we work on, and then artists or collectives work and we respect what they have been doing, and what they are doing now and what will come after. So artists continue doing what they do, which is part of our approach towards documenta. We don’t want the work to be there just for documenta — instead we try to bring documenta to the larger ecosystem, so it’s also about that relationship.

About the Author:

Tan Siuli

Tan Siuli is an independent curator with over a decade of experience encompassing the research, presentation and commissioning of contemporary art from Southeast Asia. Major exhibition projects include two editions of the Singapore Biennale (2013 and 2016), inter-institutional traveling exhibitions, as well as mentoring and commissioning platforms such as the President’s Young Talents exhibition series. She has also lectured on Museum-based learning and Southeast Asian art history at institutes of higher learning in Singapore. Her recent speaking engagements include presentations on Southeast Asian contemporary art at Frieze Academy London and Bloomberg’s Brilliant Ideas series.