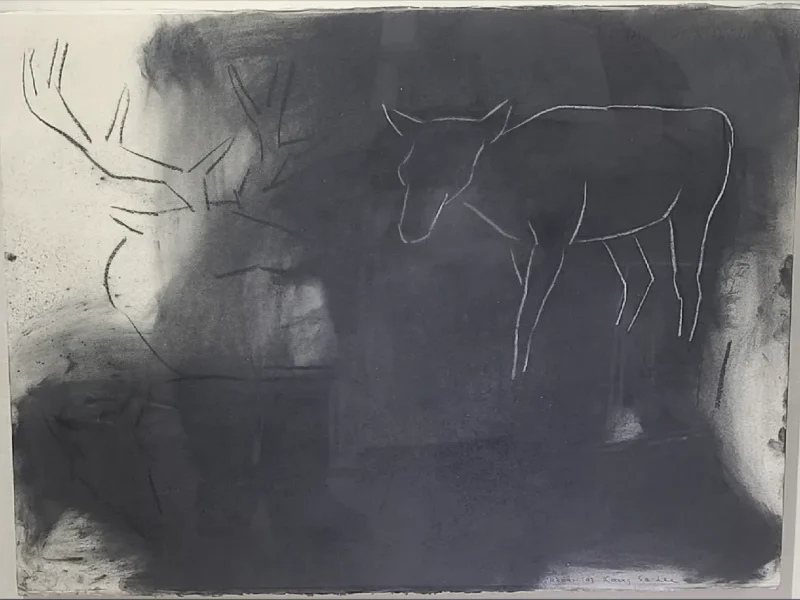

With a practice spanning drawing, painting, and sculpture, London-based Chinese artist Silia Ka Tung constructs dreamlike worlds inspired by ancient mythology and nature. Borrowing creatures, symbols and references from traditional Chinese medicine and folk stories, she invites viewers into a world of childlike wonder – where fantasy, myth and adventure collide.

In this conversation, she reflects on her early creative spark, the philosophies that guide her, and the determination that led her to become an artist.

"Maybe I held onto the childlike creativity because part of me never grew up."

What are your earliest memories of making art?

Growing up, my grandfather was the artistic director of the arts and crafts department of a government organisation in Wanzhou. I remember peeking into his room, watching him work. That image of him really stuck with me. He wasn’t just a painter – he directed theatre productions, and made clothes. Even now, I admire him deeply. That planted the seed for me, that being an artist could be a real career.

How did you go on to become an artist?

There was some initial hesitation from my family about pursuing art seriously – especially given my academic performance at the time. I wasn’t allowed to study art at school, so I started studying independently. I managed to earn high-school qualifications in art outside the regular school system, and eventually made an agreement with my parents: if I completed my formal education, I could pursue what I was truly passionate about. From that point, they became very supportive. I studied in China for a year before moving to London for my BA at Chelsea College of Art, and later completed my MFA at the Slade.

What are your greatest inspirations outside of art?

Conceptually, Chinese traditional medicine is a big influence. My father is a practitioner, so I grew up in his clinic. I was taught Qigong when I was nine. At the dinner table, we’d have conversations about the balance of cold and hot; yin and yang. They were quite casual and weren’t structured lessons at all, but those conversations shaped how I see the world. It comes through in my work: a lot of it deals with healing, plants, nature, balance.

Visually, I’m drawn to Asian pop culture like manga and video games. I wasn’t allowed to play video games growing up, but I love the ideas they contain. They bring together mythology, fantasy and adventure, kind of like a melting pot. I love how characters and storylines evolve and restart – it mirrors how I work in the studio, with multiple ideas growing at once. You also have to care for all the different parts of it to keep it growing. I like that concept behind gaming.

It seems like character play and fantasy worlds are a theme. Did you play much as a child?

Not really, because my father didn’t believe in the need for toys. I read a lot instead, mostly fiction. Even during class I’d be reading a story while sitting through geography or biology. My dad bought me educational games like puzzles, but toys and play were missing from my childhood. I bought my first cuddly toy for myself in my teens. Maybe I held onto the childlike creativity because part of me never grew up. Now, I buy lots of toys for my own kids.

Mythology seems like a common motif in your work, what kind of myths are you interested in?

I reinvent a lot of mythical creatures in my own world. They might originate in Greek mythology, but I’m interested in the same characters that appear across multiple mythologies. Like the ox god, which might appear in Indian, Mexican, or Chinese stories. Certain cultures see them as villains, but in another they are sacred gods.

I’m also obsessed with the nine-tailed fox spirit. I actually have a little shrine to her in my studio, with two figurines I bought in Japan. My daughter even made them a clay pizza offering. I’ve been reading up on the history of fox worship – how the fox spirit used to be a goddess but was later demonised, especially during the Song dynasty. It reflects how powerful female figures have often been suppressed.

“My paintings are made to connect to each other, like puzzles. They’re not fixed and can be turned any way. I often paint around the edges so they’ll visually link to other works.”

Can you tell us about the different facets of your practice?

I work across drawing, painting, and soft sculpture. Drawing started as doodles in the corners of my school books, and it’s still quite intuitive and automatic. I make very large drawings now, sometimes up to two metres.

Painting is similar but more colourful and dimensional. My paintings are made to connect to each other, like puzzles. They’re not fixed and can be turned any way. I often paint around the edges so they’ll visually link to other works.

Sculpture is more planned, and a more recent addition to my practice. I found these small dogs made of canvas at Muji, so I bought loads and painted each one. When they were grouped together, they lost their individuality – which I found really interesting. That was the beginning of the soft sculpture work.

What’s your routine in the studio?

I have two studios, a tiny one near my house in London where I make drawings, and a larger space where I make my paintings and sculptures. I work slowly – especially since having kids. I’m in the studio about four days a week now. I have an assistant once a week who helps with sewing, especially the machine work. Otherwise, I like to be in the studio by myself. Sometimes I just come to read, or I put on an audiobook.

What are you reading at the moment?

I tend to switch between books, like I do with paintings. Right now I’m reading The Myth of Sisyphus by Albert Camus – it’s helped me generate energy in the studio. I’m also listening to The Hidden Life of Trees by Peter Wohlleben, and I’ve been dipping into Postcolonial Astrology by Alice Sparkly Ka. It’s very interesting, exploring how astrology underpins a lot of our culture and mythology.

It sounds like you’re always seeking new ideas and perspectives – if you could pass some of that wisdom back in time, what would you say to your younger self?

Trust your instincts. Stay authentic. Keep creating, unapologetically. Learn to ask for help, and work as much as you can before having kids! The reward is in the making and the journey.

<Thank you so much! Visit Silia Ka Tung’s website here, and look forward to her presentation at Tokyo Gendai in September.>

Silia Ka Tung

Born in China, Silia Ka Tung has lived and worked in London since 1997. She studied painting at Chelsea College of Arts, followed by an MFA in Painting at the Slade School of Fine Art. Drawing from a wide range of ancient mythologies, her work has been exhibited across Europe and China. Through drawing, painting and sculpture, she invites viewers into a world where nature, myth, and transformation coexist without human-imposed boundaries.