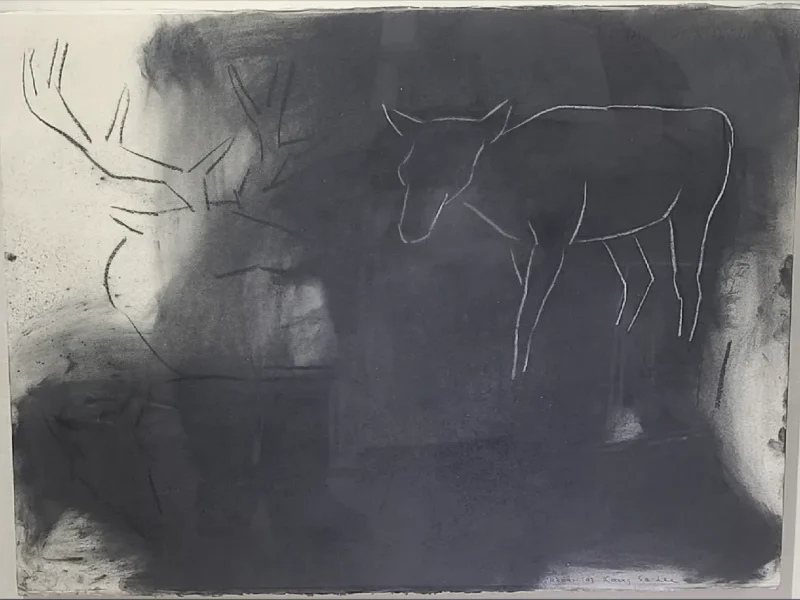

Nanae Mitobe installation view of “Trumpʼs ears are like Van Goghʼs (I also.)” 2024, HARUKAITO by ISLAND

Born in Kanagawa, Nanae Mitobe is known for her bold paintings, made by grabbing oil paints directly out of a tin can with her hands. In her early career, she became known for celebrity portraits of stars like David Bowie and Michael Jackson, but during a residency in the United States in 2014, she began creating an abstract series of anonymous faces.

Recently, Mitobe has started experimenting with installation. Often responding to social issues, her work offers a bold cultural commentary with a satirical and playful approach.

In the following interview, Mitobe reflects on how her practice has shifted over the years.

“With experience, I feel like I’ve gradually been able to overcome the challenges – mentally, physically, and technically.”

What moments do you find most enjoyable in your work as an artist, and what do you find most challenging?

It might not be the obvious kind of “fun” you find in entertainment, but for me, the moments when I zone out and look at my paintings in the studio feels most comfortable and enjoyable. I think all artists face their own kinds of challenges, and in my case they have changed over time. When I was younger, preparing work for installations felt like a huge burden, but I’ve gotten used to those tasks and feel less anxious about showing my work. Now, I spend more time on things outside of painting: research, responding to social themes, writing texts. I think it’s because I’m engaging more with society, and that brings its own challenges.

What was it that made the installation process particularly difficult for you at the time?

When I was in my 20s in the early stages of my practice, the works I was making were often incredibly physically heavy. In 2016, I held my first solo exhibition at the Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art. I had to use a crane and truck to move a one-ton piece out of my studio. I remember feeling so nervous I felt like my heart might stop.

On top of that, back then I wasn’t able to view my work as objectively. I often felt anxious about how my pieces would appear hung against white walls, and I was inexperienced with installation techniques and tools so I felt frustrated when I couldn’t achieve the setup I had imagined. With experience, I feel like I’ve gradually been able to overcome the challenges – mentally, physically, and technically.

Do you feel your creative challenges have shifted from physical concerns to how you respond to social change? How do you approach and respond to these social issues?

Yes, exactly. I initially studied traditional painting and took an academic approach to making work. But after moving to Tokyo, my environment and perspective broadened. Contemporary art is constantly evolving in response to social change. With global issues like AI and war, I feel it’s essential to keep your eyes and ears open, to sense what I should be responding to.

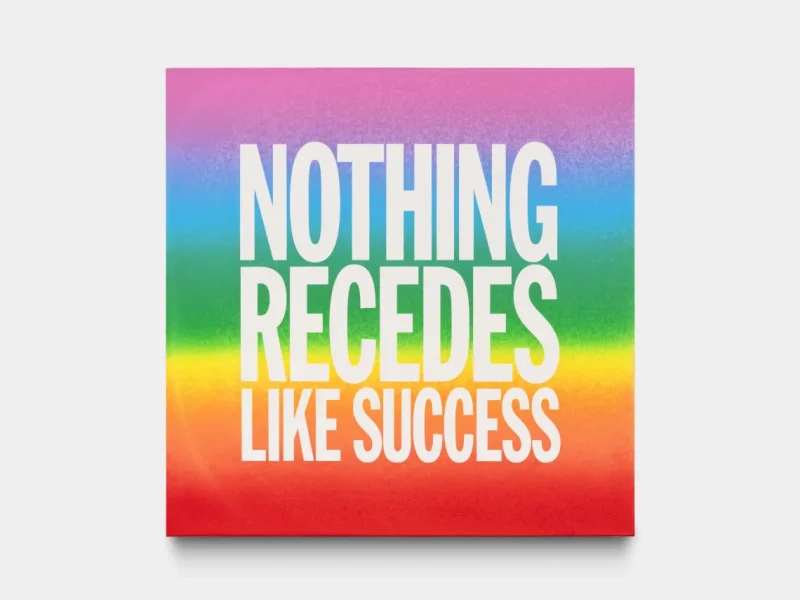

I have several exhibitions scheduled throughout each year, so it’s also important to quickly absorb the shifts in society. For the new piece I’m showing at Tokyo Gendai, I’m thinking about how to engage with the upcoming US presidential election and controversies surrounding Donald Trump. Rather than commenting on these topics directly, I try to maintain some distance and embed meaning within the work. It’s not just about making an object, it’s about what that object expresses. When I think about that, I realise how many challenges lie outside the act of making.

“Not having a routine might be my routine. I don’t keep a clock in my studio or home. I naturally ease into working depending on how I feel when I wake up”

Do you have any routines or daily habits you follow when creating your work?

I would say that not having a routine might be my routine. I don’t keep a clock in my studio or home. I naturally ease into working depending on the weather, the atmosphere of the day, or how I feel when I wake up. The time of day when I can concentrate best changes, so I intentionally avoid setting a fixed schedule for painting. That feels like a natural rhythm for me. Sometimes when I’m painting every day, I choose not to continue from the previous day but start something new, so I can approach each day with a fresh mindset.

I’m type of person who can’t stay comfortable for too long. For example, even though I’m not good at swimming, I feel the urge to try swimming somewhere once a year, or to try surviving on a deserted island, or to put myself in a place with nothing around and see what I can create. Such experiences can be a part of my research, and they are also a way to refresh my mind. I make a conscious effort to visit somewhere overseas, or in nature, or far from the city.

All this to say, I strive to always approach my work with a fresh mindset.

You had said on your YouTube channel that you used to find painting portraits difficult. Has that changed for you, either in yourself or your work?

At first, I always painted people with beautiful features. But as I continued I realised I had conflicting feelings. Part of me wanted to affirm these beautiful faces, and another part of me wanted to reject them. That tension started showing up in my paintings. One day, while painting in nature, I happened to paint this very abstract face. That moment felt incredibly liberating. Since then I’ve come to feel that through painting faces I might be able to confront or release not just my own internal struggles, but also social issues. It’s because of those experiences that I now create with the hope that there may be a way to resolve or address something meaningful in my work.

At this year’s Tokyo Gendai you’ll be presenting an installation. Compared to your previous works, has your approach or way of thinking been different?

This year I’ll be showing in a two-person exhibition with SIDE CORE, an artist collective whose work explores Tokyo and street culture. I’d seen their work before, and although it’s quite different from mine, I found the contrast in perspectives interesting. By presenting societal issues and figures tied to urban environments, we’re hoping to create a complementary dynamic between our works.

This is my first time working with this theme of the city, and figuring out how to depict vehicles, buildings, and structures has been a new challenge. I’m a painter by practice, so I have very little experience with three-dimensional forms. For this show, I’m working with sculptors to create physically durable pieces. Still, I approach them more like three-dimensional extensions of painting, so the result will be quite different from typical sculptural works.

Finally, you’re originally from Kanagawa prefecture, also home to Tokyo Gendai. Is there a place in Yokohama or the region that holds special meaning for you?

I went to high school in Yokohama, and my art prep school was also near Yokohama Station. The commute from home to school is a deeply emotional memory for me. I would buy supplies at the art store above the Sotetsu Line, walk through the underground passage, then follow the river until I got to school. That route really left an impression. Once, I bought too many materials and the bag tore, scattering my oil paints scattered all over the street, and I really struggled carrying them to class. Yokohama is where I first started painting seriously, so walking those streets evokes a quiet sense of nostalgia. It’s a path I still hold dear.

<Thank you very much! We look forward to seeing your work in September.>

Nanae Mitobe

Born in Kanagawa, Nanae Mitobe is currently based between Vienna and Japan. She graduated from Nagoya Zokei University in 2011 and studied under painter Shigeru Hasegawa. Between 2022 and 2023, she completed an exchange programme at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, where she studied under Alastair Mackinven, before graduating from the Tokyo University of the Arts in 2024 under Masato Kobayashi. In 2016 she held a solo exhibition at Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, and her painting I am a yellow was acquired by the museum in 2020. In 2022, she published her first monograph Rock is Dead. Her recent series – including Rock Star, TIME, and Picture Diary – explore the artist’s response to real-time events, from pop culture to the pandemic. Mitobe’s bold, witty and often satirical approach continues to offer a distinctive painterly lens on contemporary society.