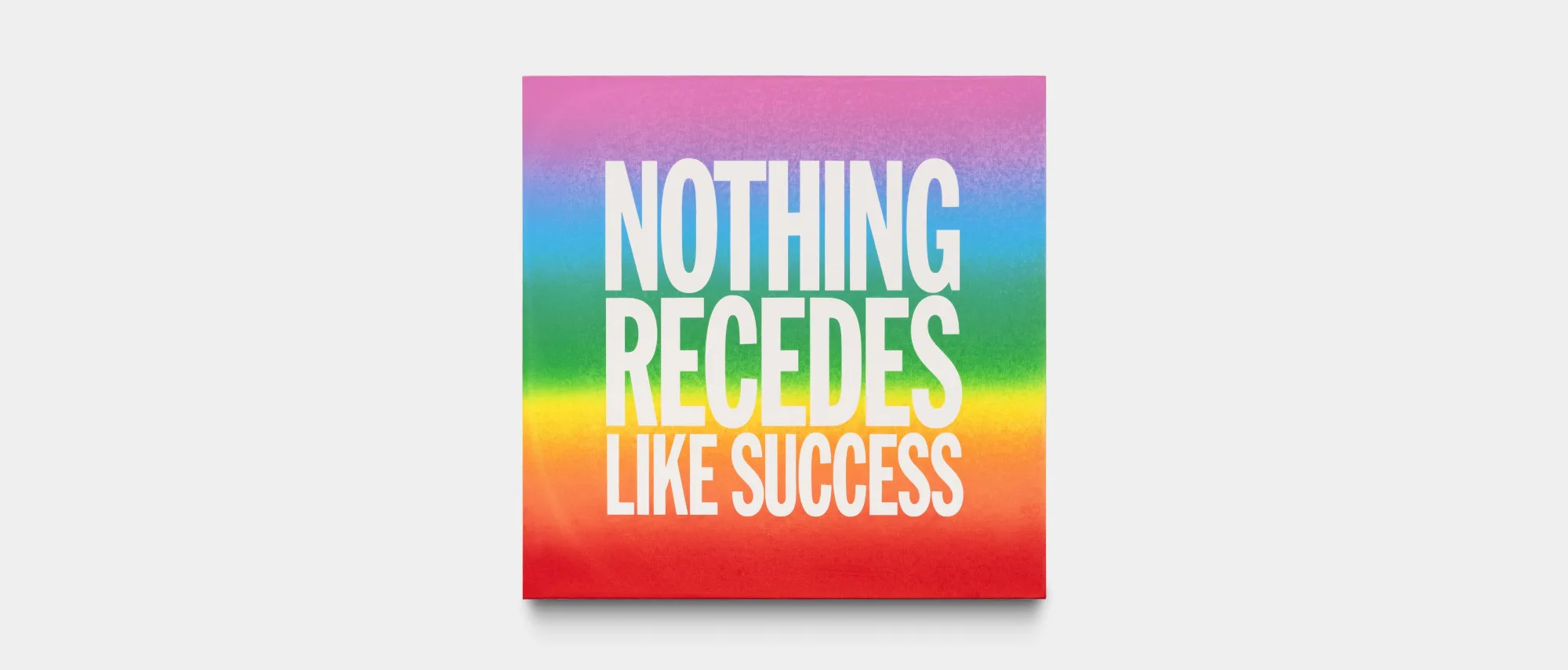

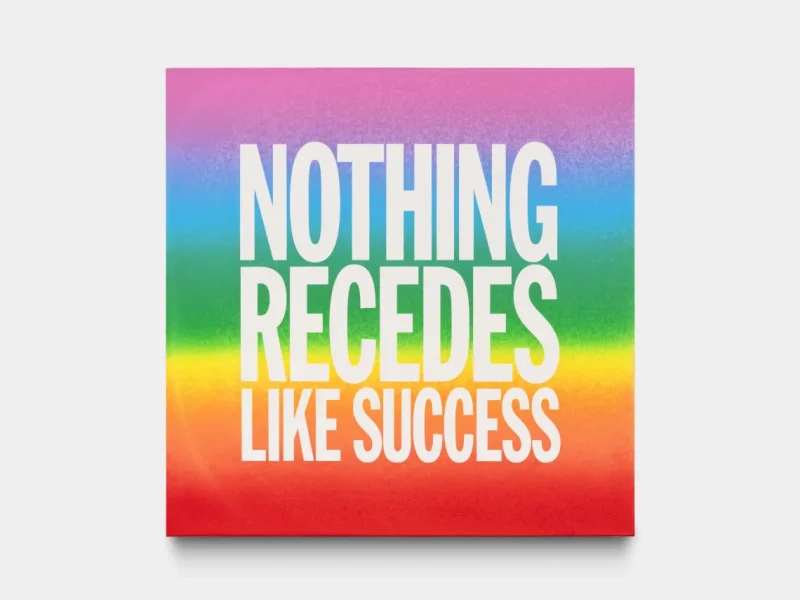

‘You’ve got to burn to shine’; ‘Thanks 4 Nothing’; ‘Life is a Killer’. These are the bold mantras painted by the iconic artist John Giorno (1936-2019). Wry and earnest in equal measure, his iconic text-based works will be exhibited by Almine Rech this September at Tokyo Gendai.

As well as being a poet and painter, Giorno was fiercely dedicated to activism and community-building. In 1965 he founded a non-profit organisation, Giorno Poetry Systems (GPS), organising community events, exhibitions and live performances.

Today, Giorno’s commitment to nurturing solidarity among artists lives on through this initiative, now led by Executive Artistic Director Anthony Huberman. The curator has worked across numerous prestigious museums and institutions, including New York’s MoMA PS1 and the SculptureCenter, as well as San Francisco’s Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts.

Here, Huberman reflects on some of Giorno’s key works, his magnetic role in the radical art scene of 1960s New York, and the importance of community during times of uncertainty.

When and why did you decide to take on this role as director of GPS?

Anthony Huberman: I came into the role in February 2023. I was drawn to the opportunity when I learned about the rich history of the organisation. John Giorno himself founded it in 1965, and in his will he specified that his legacy should be its continuation. From the beginning, GPS came out of a peer-to-peer ethos: how can an artist like John support other artists, poets, and musicians? That spirit really resonated with me. It’s about creating a culture where artists collaborate and support each other, rather than compete for limited institutional opportunities.

“People are recognising the value of artists supporting each other. That kind of solidarity feels urgent right now”

What does the nonprofit do to support that kind of collaboration?

GPS has several main areas of activity. The first is the events programme, where we invite an artist, poet, or musician to ask them to host an event about another artist whose work they admire. This might be a concert, talk series, or film screening – the formats vary. There’s also the record label, which John started in the early 1970s, inviting artists to curate a compilation LP.

Another key project is Dial-a-Poem – one of John’s most iconic works. First launched in 1968, it involved recording poetry readings by 132 writers, musicians and activists, and setting them up on a free phone line. People could call in and hear a random voice – among them Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, and Frank O’Hara – reading a poem. The original line is still running, but we’ve also set up new lines in Mexico, France, and Brazil. Coming soon are versions in Thailand, Hong Kong, Italy, and Switzerland.

The final strand is a grant programme, which we’re in the process of reviving. In the 1980s, GPS gave out money to artists living with AIDS. John would fundraise by asking musicians – people like Patti Smith and Laurie Anderson – to perform benefit concerts. That spirit of mutual aid is an important part of the organisation’s history, and we’re working to bring it back.

You’ve been working with GPS for just over two years now. Have you learned anything new about art or activism in that time?

I’ve learned there’s a huge appetite for the kind of work GPS represents – community-level gatherings and solidarity among artists. That feels especially relevant in New York, where the art world is often obsessed with power, scale, and top-down validation. GPS reminds people that artists can create culture alongside one another, they don’t always need to wait for institutions to validate their work. People are recognising the value of mutual aid, of artists supporting each other. That kind of solidarity feels urgent right now.

Did you ever have an opportunity to meet John Giorno? What did you think of him?

did meet him, in 2007, through his husband at the time, artist Ugo Rondinone. I was struck by his immense charisma and presence. Even when he wasn’t on a stage or performing, he had this magnetic energy – a warmth, a kind of gravity. You could immediately sense he was someone who could build community in the way GPS represents.

“These phrases collapse opposites: life and death; joy and suffering. He’s encouraging us to let go, and to embrace the full spectrum of life with openness and generosity”

Giorno is part of a canon of legendary New York artists, like Andy Warhol and William Burroughs. How embedded was he in that scene, and what makes his work stand out?

Giorno was very much part of that scene. He was a lover of Warhol’s in the early ’60s – in fact, Warhol’s first-ever film, Sleep (which is just five and a half hours of a man sleeping), is a film of John. He was also incredibly close to William Burroughs. In fact, the venue we use today for GPS events is actually Burroughs’ former loft. When Burroughs moved out, Giorno, who lived upstairs, bought the apartment and kept it. Now we use that space for concerts, lectures, and events. It’s a meaningful continuation of that shared history.

There are a few things that set John’s work apart. First, he was a poet who wanted to take language beyond the traditional formats – away from the printed page and out of books. Paintings belonged in museums; poetry lived in books or coffee shops. But film, telephones, performance – those were part of daily life. That’s why Dial-a-Poem is such a central work, because he used something as ordinary and ubiquitous as the telephone to deliver poetry. It was magical – art beamed into your life through something completely familiar.

Are there any other works by Giorno that you think people should really know about?

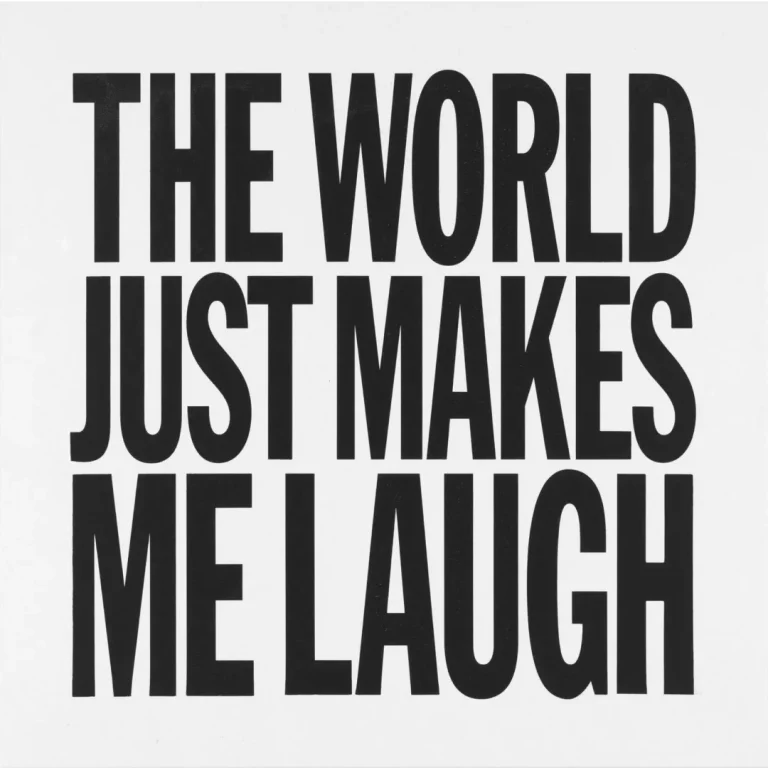

The paintings are really significant, and visitors to Tokyo Gendai will have the chance to see some of them at the fair. At first glance, they might look like just words on canvas, but they’re very much an extension of what I mentioned earlier – using the traditional language of painting and demanding that it contain poetry and language.

For anyone seeing John’s work for the first time at Tokyo Gendai, do you have any advice on how to approach it?

Approach it with joy. Many of the phrases John used – like ‘Life is a Killer’ – might sound like they’re pessimistic. But in fact, they’re deeply life-affirming. Those phrases collapse opposites: life and death; joy and suffering. He’s inviting us to recognise that these things coexist. He’s encouraging us to let go, and to embrace the full spectrum of life with openness and generosity.

<Thank you Anthony! We look forward to seeing John Giorno’s works at Tokyo Gendai.>

Anthony Huberman

Anthony Huberman (b. 1975, Switzerland) is a curator and writer based in New York. He currently is the Executive Artistic Director of Giorno Poetry Systems, a nonprofit organization, founded in 1965 by the artist John Giorno, where artists, poets, and musicians reflect on the work of other artists, poets, and musicians. Previously, he was Director and Chief Curator of the Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts in San Francisco, Founding Director of The Artist’s Institute in New York, Curator at Palais de Tokyo in Paris, Curator of SculptureCenter in New York, and Director of Public Programs at MoMA PS1 in New York.