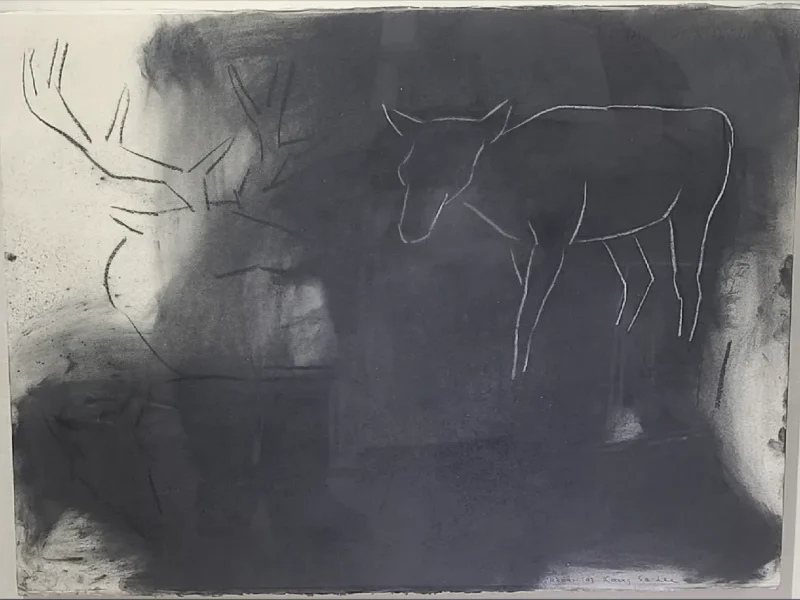

Scottish artist Katie Paterson explores themes of time, geology, and the cosmos – vast subjects that she interrogates through poetic and often participatory artworks. The concept of Deep Time – the unimaginably vast timescales of Earth’s history – is central to her practice. From melting glacier records to a century-long library project, her work encourages viewers to connect with the natural world and consider their place within it.

This September, Paterson will present her work with Ingleby Gallery at Tokyo Gendai. In this interview, she reflects on the primordial landscapes that shaped her outlook, and how art can collapse abstract concepts into sensory experiences.

“I see artistic practice as a way of engaging with larger questions about Earth, time, and our place in the universe”

Your work explores the idea of ‘deep time’ – a topic that first came to your attention while working as a chambermaid in the remote north of Iceland. What was it about this landscape that triggered your interest?

Immersed in that primordial landscape – surrounded by the midnight sun, exploding geysers, volcanic strata, and all-enveloping light – I became acutely aware that we live on a planet. Time seemed inscribed into the very place itself, revealing a sense of vastness and duration embedded in nature. This experience tilted me on my axis and set me on a path of exploring how to tell the story of deep time through art.

Phenomena like the midnight sun skimming the horizon and bouncing back – a rhythm I had never known before – made me realise our planet is just one among billions. The visible geological strata in the rocks and the immense, almost timeless remoteness of the landscape offered a direct link to deep time, a perspective later deepened through my interest in glaciers and stars.

How did your upbringing in Scotland inform your interest in geology and time?

Growing up surrounded by Scotland’s ancient weathered landscapes and rich biodiversity shaped my awareness of time, geology, and place. The standing stones scattered across the country, layered rock formations, and enduring cultural traditions all offered a quiet but powerful sense of history and the shifting rhythms of nature. There’s a stillness in those landscapes – a vastness – that invites reflection on the Earth’s slow transformations: how rocks hold aeons, how light moves across moorland, how erosion silently marks time’s passage.

These experiences gave me a sense of connection to the planet’s past and laid the foundations for how I now see artistic practice: as a way of engaging with larger questions about Earth, time, and our place in the universe. That fascination with the scale of existence, I believe, can be traced right back to my roots in Scotland.

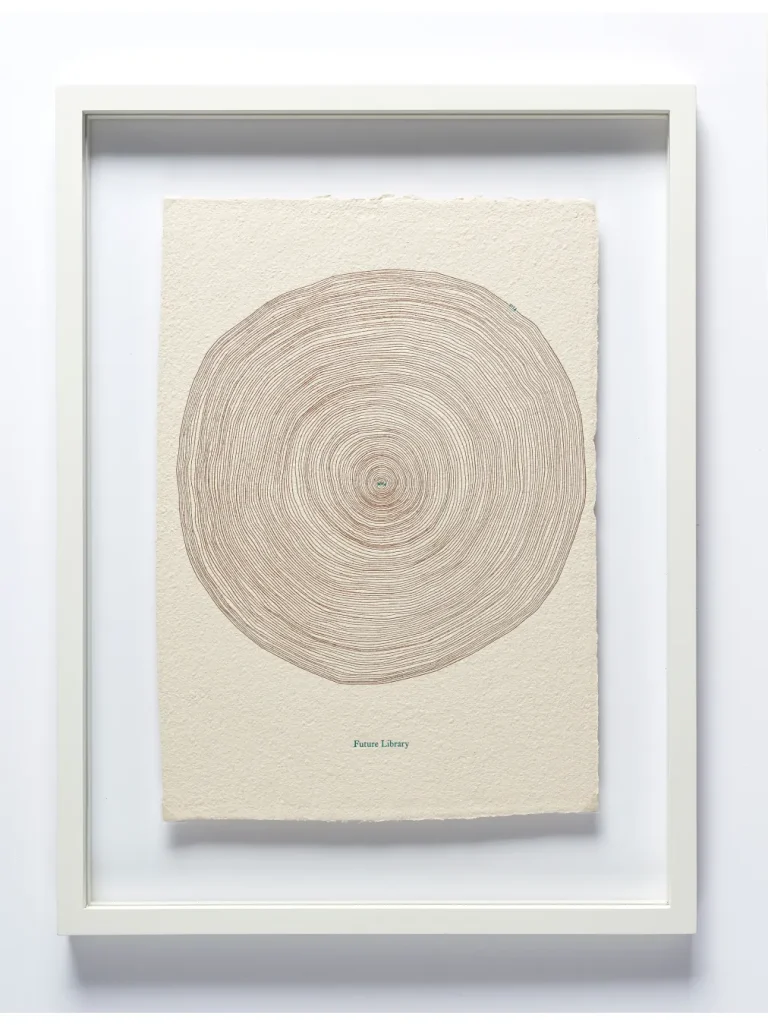

Future Library (2014, below) is a unique work of art in which you invite one writer per year to contribute an unpublished manuscript to a library in the Norwegian forest. These are left unread until 2114, when they will be printed on paper made from trees planted in the forest. How does it feel to create a work that you will never see completed?

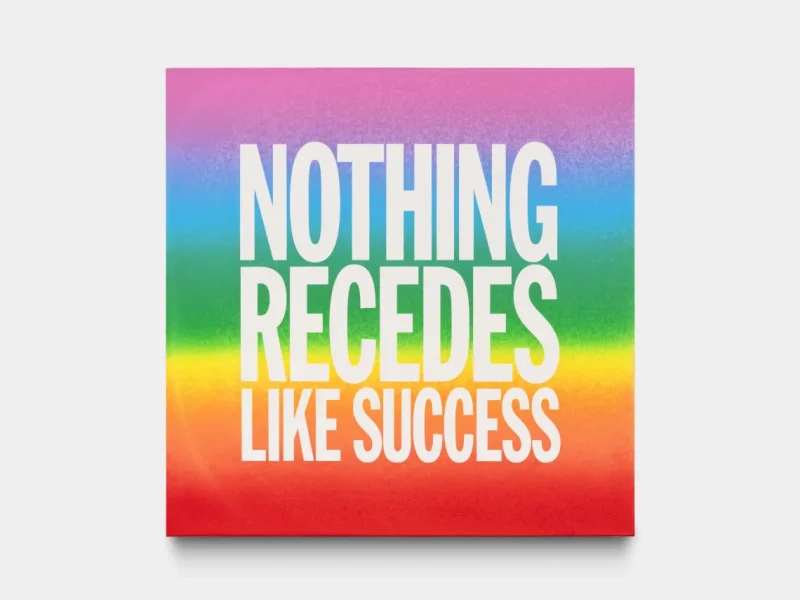

Creating the Future Library brings a deep sense of humility and wonder, a feeling of being part of something much larger than myself. It’s both humbling and hopeful. The project unfolds over a slow timespan, inviting us to think not in days or years, but in decades and centuries. Rooted in faith, trust, and patience, its culmination lies beyond my own lifetime.

There’s something powerful in creating an artwork I will never see completed. It removes ego from the process and shifts the focus to time, care, and continuity. In a world that moves so quickly, Future Library offers a quiet resistance – a space for reflection and long-term thinking. It is an act of imagining and tending to the future: an artwork that asks its creators and contributors to embrace uncertainty and place trust in the creativity, stewardship, and curiosity of future generations.

The themes you explore are existential – with that in mind, are you hopeful about humanity?

Despite working with themes of deep time, disappearance, and environmental crisis, I do have hope. Projects like Future Library are, at their core, acts of optimism – rooted in trust, care, and belief in generations to come. Planting a forest and entrusting words to an unknown future is itself a gesture of hope.

For me, art is a way of nurturing possibility and encouraging new narratives. I believe our capacity for creativity, empathy, and imagination offers genuine reasons for optimism, even in difficult and uncertain times. We are part of a continuum, connected to those who came before and after us, and I trust that people will continue to care for the planet and each other.

“Art has the power to collapse vast, abstract concepts – like geological time, cosmic distances, or ecological cycles – into embodied, sensory experiences.”

Your work is poetic and philosophical. How does art offer a different kind of knowledge or insight, than science or language alone?

Art has the power to collapse vast, abstract concepts – like geological time, cosmic distances, or ecological cycles – into embodied, sensory experiences. By doing so, it enables people to engage with the world not just intellectually, but emotionally and intuitively as well. This kind of understanding differs from scientific or linguistic knowledge. Through material, form, and experience, art can make the unimaginable approachable, and the distant immediate.

Artistic practice opens up space for ambiguity, possibility, and wonder – qualities that might not always have a place in scientific discourse. It provides a way of representing things we can’t fully grasp, transforming our relationship to phenomena and allowing knowledge to be felt, sensed, and lived. For me, art is a language that connects the personal to the universal – merging deep time with individual experience, and allowing for ‘thought experiments’ and imaginative leaps that bypass the boundaries of conventional understanding.

Your work is conceptual – do you see a right or wrong way of interpreting it?

I don’t see a right or wrong way to interpret my work. Each person brings their own history, perspective, memories, and associations. The artworks are open and invite multiple readings. My aim is to offer space for personal reflection, whether it leads to poetic, philosophical, scientific, or deeply personal responses. Ideally, they invite people to feel – to connect emotionally with ideas that often seem abstract or distant. If a work evokes emotion, sparks a new way of seeing or thinking, or simply creates a sense of presence in the world, then it has fulfilled its purpose.

What do you hope viewers will take away from the experience?

I hope viewers come away with a sense of wonder, curiosity, and interconnectedness. Whether the work speaks to deep time, the cosmos, extinction, or the rhythms of the Earth, my intention is to create experiences that open up space for reflection, awe, and at times, humility.

<Thank you very much! We look forward to seeing your work in September.>

Katie Paterson

Katie Paterson (b. 1981) is a Scottish artist known for poetic, conceptual works that explore time, space, and the cosmos. She creates deeply imaginative projects that connect viewers to geological time. Represented by Ingleby Gallery, Edinburgh, and James Cohan Gallery, New York, her work has been exhibited globally and is held in major public and private collections.