As a student, Satoru Aoyama found himself studying textiles by chance. Though challenging at first, he eventually found his footing and embraced it into his practice. Now, he continues to work with the same industrial sewing machine from the 1920s, exploring labour, protest, and capitalism. In this interview, Aoyama reflects on his formative years of studying in London, the critical role embroidery plays in his practice, and his reflections on Tokyo Gendai, where he returns this September with Mizuma Art Gallery.

“No matter the setting or context, I always strive for my work to carry a sense of critique”

You majored in textiles at university. What led you to choose that field?

I studied at Goldsmiths, University of London, and the visual arts department only offered two pathways: fine art or textiles. The fine art course was known for its emphasis on conceptual art, while textiles was rooted in feminist approaches, and traditionally associated with women’s practices. I originally applied for fine art but ended up on the textiles course after being placed on the waiting list. A professor recommended it to me. They told me that textiles might suit me, based on how I dress. I later realised that personal tastes in fashion have nothing to do with textiles, but at the time I accepted without dwelling too much on it, thinking that maybe it’s not so bad to learn about fashion design.

What stood out to you from your time studying in London? Do you ever think about returning?

There’s a common saying that getting into a university in the UK is easy, but graduating is hard, and in my case that was definitely true. I failed my first year, even though I attended classes regularly. Part of it was the language barrier, but the main reason was that I completely misunderstood the context and meaning behind textile art. For example, one of my first projects was a sculpture meant to visualise cigarette smoke – the kind of thing that is quite typical for a first year art student. Unsurprisingly, it didn’t resonate at all. The department was almost entirely made up of women, and I was one of only two male students (the other was from Hong Kong). We both ended up failing that first year together. From then on, I realised that if I wanted to survive in that environment, I’d have to work twice as hard. When I repeated the year, I made sure to arrive at the studio earlier than anyone else and stay later than anyone. If I had an essay to write, I’d work on it from morning until night. Honestly, the biggest thing I learned from studying abroad was the importance of diligence – sorry if that’s a boring answer! I do want to return to the UK someday, but I don’t think I could live the way I did as a student. Ideally, I’d go back if I was had a lot of money, but in today’s London, that feels difficult.

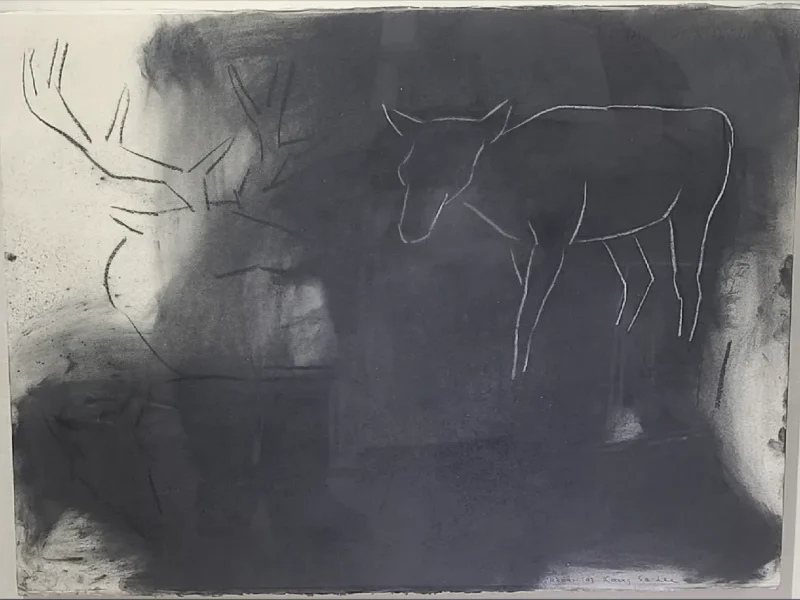

![News From Nowhere (Labour Day) [detail], 2019, Embroidery and drawing on silkscreen print 100 × 140 cm, Private collection © AOYAMA Satoru, Courtesy of Mizuma Art Gallery, Photography by MIYAJIMA Kei](https://tokyogendai.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/webpage-SA-768x512.webp)

Embroidery has been a consistent feature of your work. Why is that? How does it function in your practice?

Since I was at university, I’ve been working with this industrial sewing machine made in the 1920s. Using that machine, and engaging with all its historical context, has led me to topics I previously knew little about: the development of capitalism, changes in labour systems, gender roles, and more. These discoveries feed directly into my work, and often become the themes for future projects. So the act of sewing isn’t just a method – it’s a way of thinking and researching.

How do you choose the materials you work with, and how do you approach the process of stitching into them?

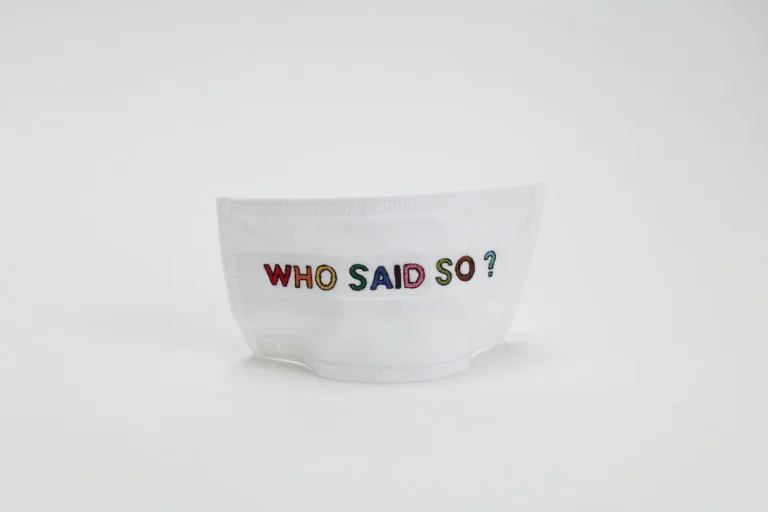

In the past, I often used a semi-transparent polyester organza as a base fabric, covering it so densely with embroidery that the cloth would disappear entirely. But during the pandemic, I began stitching text directly onto ready-made objects like masks and shirts. That shift inspired me to think more freely about materials – I now embroider on anything that can be sewn onto. Each surface creates different visual results, so I choose materials depending on the concept and imagery I want to convey. For example, when I stitch detailed images onto something like organza, it can look surprisingly realistic – almost photographic. When I sew onto paper, the stitching can cause it to tear. In that case, I reinforce it from behind with another layer of paper. This creates a thickness in certain areas, giving the work a kind of low-relief texture.

“In recent years, I realized I’m creating small monuments of things that are invisible or becoming obsolete, using tools that are themselves obsolete.”

Your works often depict scenes related to protests or labour movements. Could you tell us more about why these motifs appear in your work?

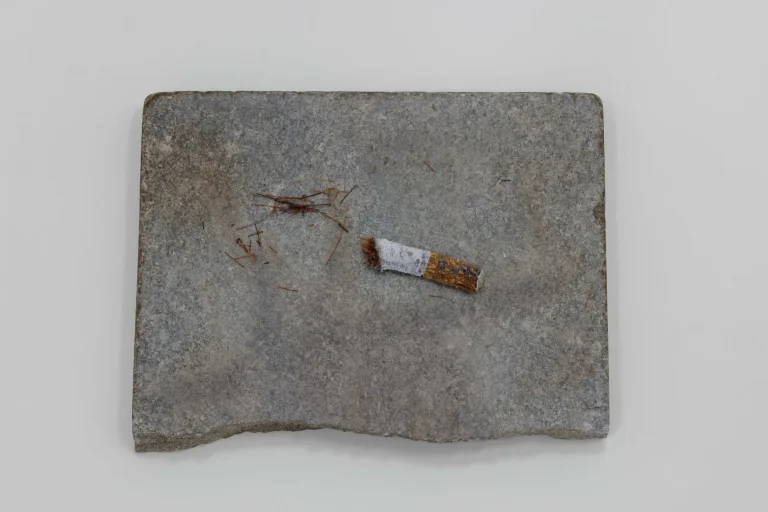

Whether it’s a depiction of a protest or a quiet landscape of a sunset, the underlying theme in all my work is the same: a reflection on things that are disappearing or invisible in contemporary society. That includes jobs and human labour that are being replaced by new technologies like AI. Even the old sewing machine I use is a discontinued tool. In recent years, I realized I’m creating small monuments of things that are invisible or becoming obsolete, using tools that are themselves obsolete.

You’ll be showing at Tokyo Gendai this year. What are your hopes or thoughts about participating?

Tokyo Gendai is a much-needed platform for contemporary art in Japan, and I truly hope it continues for years to come. As an artist, I believe the best contribution I can make is to keep presenting strong, thoughtful works. When I participated two years ago through Mizuma Art Gallery, I chose to exhibit a piece depicting a small cigarette butt [editor’s note: image above] in the corner of the booth – so discreet that almost no one would notice it. The motif was based on the last cigarette smoked by my neighbour, a former factory owner who had quietly faded away into the margins of capitalism. No matter the setting or context, I always strive for my work to carry a sense of critique.

<Thank you very much! We look forward to seeing your work in September.>

Satoru Aoyama

Born 1973 in Tokyo. BA in textiles from Goldsmiths College, University of London in 1998; MFA in fiber and material study from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2001. Lives and works in Tokyo. Employing industrial-use sewing machines, Aoyama presents numerous works which expand the frame of the embroidery medium, by questioning the values inherent in humanity and labour within the continuing changes effected by modernization. Some of Aoyama’s recent major exhibits include “Unfolding: Fabric of Our Life” (Center for Heritage Arts & Textile, Hong Kong, 2019) , “Re construction” (Nerima Art Museum, Tokyo, 2020), “A Boy Who Sews Forever” (Meguro Museum of Art, Tokyo, 2024) etc.